This was never supposed to happen.

So how do you go from dealing with a public utility that has to be dragged kicking and screaming through decades of litigation just to get it to fix a public health disaster it inadvertently created to having that same utility embrace and manage an elaborate set of wildlife and bird habitats, complete with public access to invite people into this strange but beautiful place? You do it with data, you do it with heart, and you do it with years of dogged persistence.

So how do you go from dealing with a public utility that has to be dragged kicking and screaming through decades of litigation just to get it to fix a public health disaster it inadvertently created to having that same utility embrace and manage an elaborate set of wildlife and bird habitats, complete with public access to invite people into this strange but beautiful place? You do it with data, you do it with heart, and you do it with years of dogged persistence.

That somewhat oversimplifies the process by which we arrive today (tomorrow, technically, for the public dedication), at the opening of the Owens Trails at Owens Lake in the Eastern Sierra, but the transformation has been dramatic and quite possibly unprecedented. Los Angeles Department of Water & Power, who was never legally required to do anything but mitigate blowing dust at Owens Lake, is well into construction of seven different habitats or “guilds” on and around the lake, in cooperation with Audubon California, to meet the migratory needs of the hundreds of thousands of birds who use Owens Lake as a critical stopover on the Pacific Flyway. And they’ve included beautifully designed public access areas and trails so that the public can come to the lake to see the extraordinary place it is.

This is a Big Deal. One that’s almost impossible to overstate.

I’ll get into what’s happening now, but first, a little history (because context is important).

The lake itself has been transformed and exploited for over a century. In the late 1800s, it supported huge steam-powered barges carrying ore and other materials being mined from the Inyo Mountains that flank its eastern shore. Just before the turn of the century, lake levels had dropped too low to allow the steamers to cross—this was partially a result of local farmers drawing water from the Owens River via irrigation canals they dug (many people have dipped their straws into the Owens River for many years, for many purposes).

And then most notoriously, along came William Mullholland and his Los Angeles Aqueduct. Completed in 1913, it diverted the entirety of the Owens River north of Independence into the aqueduct—it made possible the city of Los Angeles that exists today, but almost (the “almost” is important) killed Owens Lake, a terminal lake at the southern end of the Owens Valley, which had mostly dried up by 1926. Once the lakebed was exposed, it was exploited still more by companies who mined the lake itself for its precious minerals. The U.S. Borax/Rio Tinto surface mining of the mineral trona continues today, in fact.

The result of the lake’s deterioration was chronic and toxic blowing dust, which was the worst source of air pollution in the entire United States and a serious threat to public health. Litigation commenced in the 1970s to force LADWP to mitigate the blowing dust, and over the years, beginning in 2001, various mitigation measures were put in place at the lake—some more successful than others (blowing dust has now been reduced by 95%, which is a good thing, and means the mitigation measures have paid off). In addition to the mitigation efforts, something else significant happened—in 2006, LADWP, under court order, began sending water back down the lower Owens River below the aqueduct for the first time since its construction. The result of those two things meant that there was finally water—carefully controlled and gridded off—on the lake for the first time in almost a century.

Now, Owens Lake was never completely dry. It is ringed with a series of springs and seeps along its western shore which kept an active marsh and grassland area alive on the lake. With the addition of the water on the lake itself, limited though it was, the birds came back. And they came back in massive numbers, and did so with a rapidity that surprised just about everyone. But it was one key species that really got everyone’s attention—the tiny snowy plover. A state species of special concern because of rapid habitat loss, it was this small shorebird’s presence at the lake that got relevant parties to really take a closer look at what was happening with bird life on the lake. In a few short years, Eastern Sierra Audubon, a new chapter of Audubon California, was founded, and the State Lands Commission and Department of Fish & Wildlife, among others, were actively documenting and lobbying for the bird life on the lake.

National Audubon subsequently designated the Owens Lake an Important Bird Area (IBA) on the Pacific Flyway (a critical migratory route); a group of local stakeholders and activists in 2007 formed what would become known as the Master Plan working group, and they succeeded in bringing LADWP to the table to begin work on preserving this accidentally resurrected habitat.

Keep in mind, LADWP’s responsibilities to the Owens Valley were never supposed to include habitat management. Even getting this far was significant. Michael Prather, a local conservationist and co-founder of the Eastern Sierra Audubon chapter and who has been one of the lake’s most important advocates, recalls that “We discussed two main areas of interest—saving water and protecting habitat. DWP told us that if we could save water by creating certain habitats, then they would be able to convince their decision makers to support that.”

Prather continued: “Around 2012–2013, LADWP announced that due to time obligations for its dust control, it needed to move more quickly or suffer penalties from GBUAPCD (the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, who monitors pollution levels at the lake) and would proceed alone. DWP assured the stakeholders that what was in the draft Master Plan would be incorporated into what they now call the Master Project. The advisory committee and the work groups would still meet and advise the DWP in its work.”

In 2013, however, LADWP ended up back in litigation with Great Basin and other parties. This skirmish took more than a year to resolve, which resulted in a lengthy stretch of radio silence that caused a lot of people (including yours truly) to worry that they’d abandoned their commitment to the lake. Behind the scenes, they were still working with Audubon, and, Prather says, once a settlement was reached in the litigation, the Master Project and stakeholder participation resumed. (Whew!)

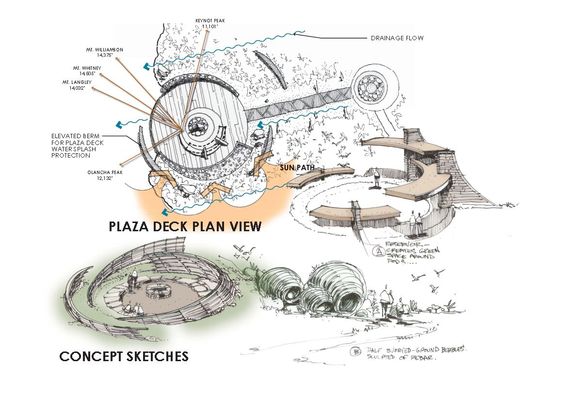

LADWP released its outline of the Master Project in spring 2013 (which you may have seen in some of my older posts on this blog), announcing their commitment to the construction and management of the seven habitat guilds, as well as public access areas to allow people to enjoy the impressive bird life at the lake. Over the next three years, the Los Angeles-based firm NUVIS Landscape Architecture was awarded the bid to design and build, along with LADWP, the public access areas at the lake. Their design is beautiful, and in perfect harmony with its environment. Construction commenced and was completed on schedule, and the area will have its grand opening tomorrow, April 29, 2016.

This is a compromise, but it’s a good compromise that will be very good for wildlife. Those who argue that LADWP should just dismantle the aqueduct and refill the entire lake will not see that happen, at least not in this lifetime. We’d all love to see the lake restored, but Los Angeles not only will not, but really cannot, abandon its water supply. And there are more complicated issues in addition. Much of the lakebed is considered a disturbed landscape—it is unrestorable. Soil quality is so poor that no vegetation will grow in many places in and around the lake (LADWP has had success with growing native saltgrass in several places as part of their mitigation efforts, but that’s been hit or miss). The mining interests, like it or not (I happen to NOT like it), hold legal contracts that allow them to continue their removal of minerals for years into the future. The lake is a big, beautiful mess, and multiple entities both public and private will fight tooth and nail to maintain their hold on the lake—and for now this compromise is the best solution for all parties (and honestly FAR more than I ever expected wildlife would get from LADWP).

I’ll repeat this part: this was never supposed to happen, and it’s a BIG DEAL. This, the habitat creation and management. This, the welcoming of the public to the lake. This is a huge victory for the groups in the Owens Valley who fought so tirelessly to make this happen. That’s the story so many in the media have completely missed in their obligatory coverage of the Owens Trails, and it’s a truly important story.

“I am elated!” Prather told me. “I never dreamed that we would ever have gotten this far. For so many years I worried about how we would protect the birds that had returned. How could we protect the heritage wildlife population that was back again?”

LADWP, who fought long and hard to avoid its obligation to mitigate dust at the lake for so many years, has undergone a pretty radical change in corporate culture. The entity who for years reminded the interest groups that habitat was not their responsibility now employs a staff of biologists who monitor wildlife on all LADWP land in the valley, and not just at the lake. The entity who has so often refused to do anything without a court order and under threat of severe financial penalties has worked with Audubon and established critical habitats for migrating birds. LADWP is reviled in the Owens Valley, and for good reason. But just this once, they deserve a pat on the back. They have done a very good thing for the Owens Valley. And the groups who have worked so hard to make this happen should feel immense pride. Thank you for this tireless, impassioned work you have done—for you have achieved the impossible.

My own personal note: I am amazed and so thrilled with what’s happening at the lake right now. Having spent the last six-plus years of my life documenting the birds that returned to Owens Lake, this feels very personal to me (in the best way). I also want to give a huge thank-you to Mike Prather, who was gracious enough to be interviewed for this piece. When I first began poking around the valley and bugging people about my lake project, every single person told me “You need to talk to Mike Prather!” They were right. Nobody knows the lake better or gives more of his time to groups all over the state to educate them about the lake than he does, and I am just one of so many who have been the recipient of his generosity with his time and knowledge. His help has been invaluable, and he has become a valued friend. The birds thank you, too, Mike!

One Comment

Carol Cantino

This is happy news…very happy news. Thank you so much, so very, very much to all the people who have fought so hard to restore habitat for our birds. The history of Owens Lake, Owens Valley and the Water is fascinating. Determined, tough minded people fighting an uphill battle—-and winning! Congratulations! Everybody wins…especially the birds.